Signals from the brain’s amygdalae make it more difficult for anxious and stressed children to regulate their emotions, a study shows.

The findings, which appear in Biological Psychiatry, come from the first study to use brain scans to examine how anxiety and chronic stress change emotion-regulation circuits in children. The children in the study were 10 or 11 years old, a developmental stage when vulnerability to mood-regulation disorders, such as anxiety and depression, becomes entrenched.

“…the communication between our emotional centers and our thinking centers becomes less fluid when there is significant stress.”

The study used functional magnetic resonance imaging to examine the nature of the signals between two parts of the brain: the amygdalae, almond-shaped nerve clusters on the right and left sides of the brain that function as its fear centers; and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a brain region involved in executive functions such as decision making and emotion regulation.

“The more anxious or stress-reactive an individual is, the stronger the bottom-up signal we observed from the amygdala to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex,” says the study’s senior author, Vinod Menon, professor and professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Stanford University School of Medicine. “This indicates that the circuit is being hijacked in more anxious children, and it suggests a common marker underlying these two clinical measures, anxiety and stress reactivity.”

Victor Carrion, a coauthor of the study and professor of child and adolescent psychiatry, says, “This study shows that the communication between our emotional centers and our thinking centers becomes less fluid when there is significant stress. You want that connection to be strongly signaling back and forth. But stress and anxiety of a certain level seem to interrupt that process.”

Carrion is the director of the Stanford Early Life Stress and Pediatric Anxiety Program, and is professor for child and adolescent psychiatry.

Aversive images and anxious kids

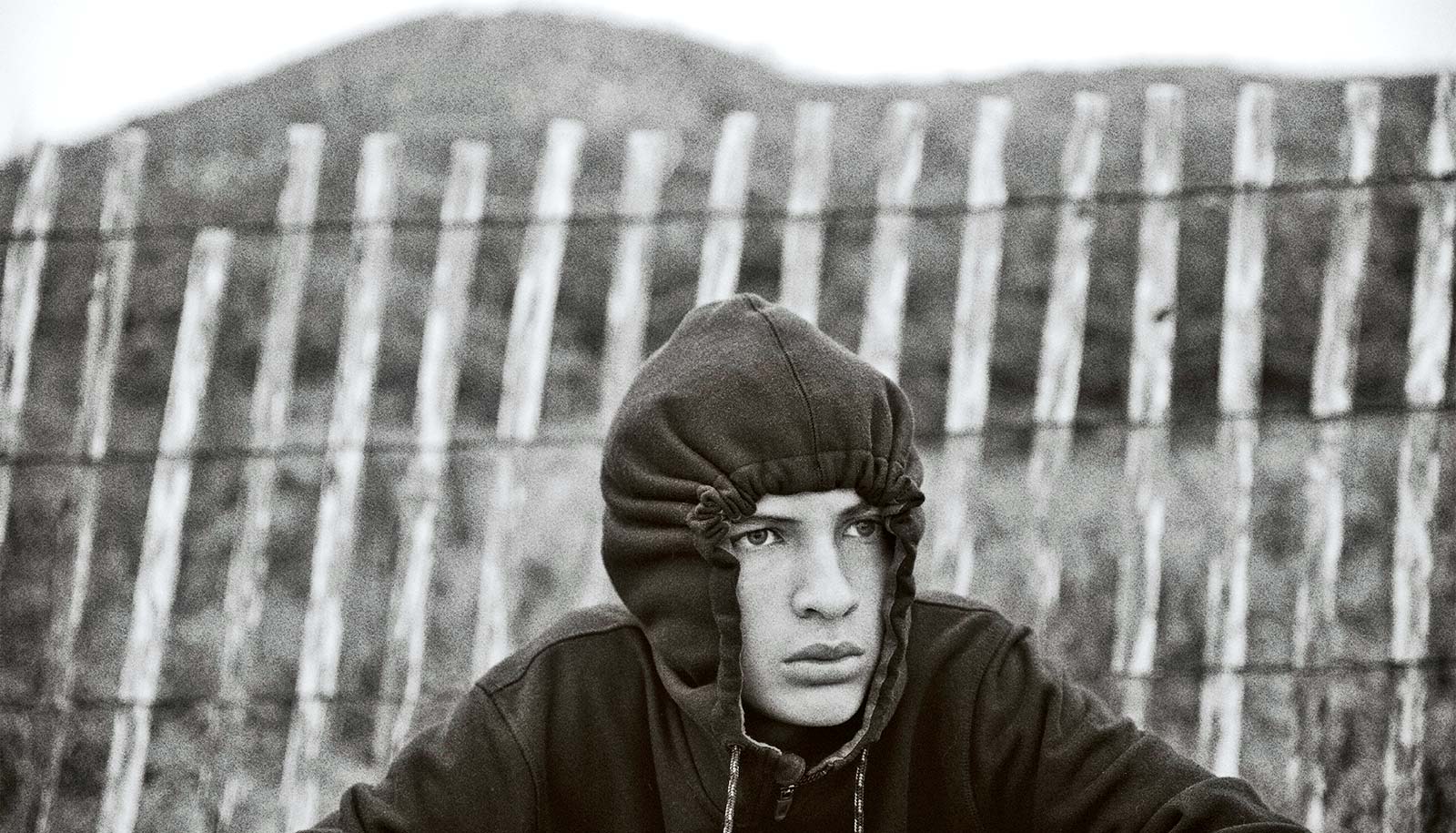

The study included 45 students in a California community with predominantly low-income residents who often face high levels of adversity. All 45 children had their anxiety levels and stress responses measured using standard behavioral questionnaires. Although their exposure to stress was potentially high, none had mood disorder diagnoses.

To test how the children’s brains responded as they were trying to regulate negative emotions, the scientists conducted functional MRI scans while the study participants looked at two types of images, neutral, and aversive. Neutral images showed pleasant scenes, such as someone taking a walk, whereas aversive images showed potentially distressing scenes, such as a car crash.

The children received instructions about responding to each image. For all the neutral images and half the aversive images, they were asked to look at them and respond to them naturally, rating their emotional state on a numerical scale after seeing each one. They were asked to look at the other half of the aversive images and try to reduce any negative reactions they had by telling themselves a story to make the pictures seem less upsetting — a story such as, “This car crash looks bad, but the people in the vehicles weren’t hurt.” After the kids tried to modify their emotional reaction, they again rated their emotional state on the numerical scale.

As the researchers expected, the children reported less negative emotions after being asked to reappraise their reactions to aversive images.

Using the brain-scan data, the researchers tested the strength and direction of interactions between the amygdala, the fear center, and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the reasoning center, while the children viewed the images. Although the children with different levels of anxiety and stress reactivity reported similar reductions in their negative emotions when asked to reappraise the aversive images, their brains were doing different things.

When to intervene?

The more anxious or stressed the child, the stronger the directional signals from the right amygdala to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. No such effects were seen in the reverse direction—that is, there was no increase in signaling from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex to the amygdala. Higher levels of anxiety were associated with less positive initial reactions to aversive images, less ability to regulate emotional reaction in response to aversive images, and more impulsive reactions during reappraisal of aversive images. Higher stress reactivity was linked with less controlled, more impulsive reactions when reappraising aversive images, suggesting that the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is less able to carry out its job.

The findings reveal how anxiety can change the brain, and act as a baseline for future studies to test interventions that may help children manage their anxiety and stress responses, the scientists say.

“We need to be more mindful about intervening,” Menon says. “These results show that the brain is not self-correcting in anxious children.”

“Thinking positively is not something that happens automatically,” Carrion says. “In fact, automatically we think negatively. That, evolutionarily, is what produced results. Negative thoughts are automatic thoughts, and positive thoughts need to be practiced and learned.”

This work took place in partnership with the Ravenswood City, Alum Rock, and Orchard school districts and Pure Edge Inc., which provides mindfulness curricula for children. The work had support from the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health, the National Institutes of Health, the Stanford Maternal Child Health Research Institute. and the Stanford Institute for Computational & Mathematical Engineering.

Source: Stanford University